.

7/17/2018, “‘He is honest–but smart as hell’: When Truman met Stalin,” Washington Post, Kristine Phillips

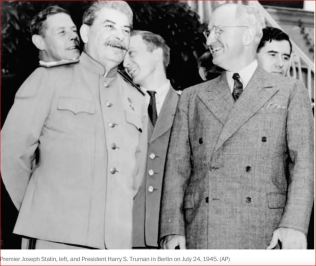

“Premier Joseph Stalin, left, and President Harry S. Truman in Berlin on July 24, 1945. (AP)”

“Premier Joseph Stalin, left, and President Harry S. Truman in Berlin on July 24, 1945. (AP)”

In a letter to his mother and sister, Truman called the Soviets “pigheaded” and difficult to work with, said Sam Rushay, historian and archivist at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum in Missouri. But at least one man, however, was different in Truman’s mind, and that was Joseph Stalin, the Soviet Union’s communist leader

“I can deal with Stalin. He is honest-–but smart as hell,” the 33rd president of the United States wrote in a diary entry dated July 17, 1945, the first day of the Potsdam Conference in Germany. Truman was meeting with his fellow Allied leaders — Stalin and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill — to negotiate the terms of the end of World War II. Germany had surrendered about two months earlier, and the leaders needed to agree on postwar reparations from the country.

When Truman met Stalin that day…,he had been president of the United States for only three months. And before that, he’d been vice president for only 82 days. His relationship with his predecessor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, was nearly nonexistent, and he had been kept in the dark about end-of-war negotiations that he was now taking part in.

Just hours after Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, Truman took the oath of office and asked a gaggle of White House reporters to pray for him.

“Truman approached that meeting with a great deal of anxiety and insecurity….He was very poorly informed about the complexities of the agreements that President Franklin Roosevelt had worked out during the war with Stalin,” said Melvyn Leffler, a University of Virginia historian and author of “A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration and the Cold War.”

Truman also had just recently learned the full details of the country’s secret atomic-bomb program, the Manhattan Project, which the president had hoped would lead to Japan’s surrender and, ultimately, the end of the war. Leffler said there was a “tremendous uncertainty and ambiguity” about whether the bomb was viable. By the time Truman arrived in Germany, he knew the bomb worked.

“The dramatic success of the atomic bomb testing tremendously shaped Truman’s…approach toward the conference and toward the substantive negotiations,” said Leffler, a visiting professor at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center.

Most important for Truman, Leffler said, was to get confirmation from Stalin that the Soviet Union would go to war against Japan.

On July 24, 1945, as the Potsdam Conference entered its second week, Truman told Stalin about the weapon, though he did not mention it was an atomic bomb. After a meeting, he walked around the round table to talk to the Soviet leader.

“I casually mentioned to Stalin that we had a new weapon of unusual destructive force,” Truman said.

Stalin’s reply, according to Truman: He hoped the United States would make “good use of it against the Japanese.”

By many accounts, Truman saw Stalin as a cordial ally.

“I like Stalin,” he wrote in a July 29, 1945, letter to his wife. “He is straightforward, knows what he wants and will compromise when he can’t get it.”

Truman also invited Stalin to the United States and said he would send the USS Missouri for the Soviet leader. He wrote in a diary entry dated July 18, 1945:

“He said he wanted to cooperate with U.S. in peace as we had cooperated in War but it would be harder. Said he was grossly misunderstood in U.S. and I was misunderstood in Russia. I told him that we each could help remedy that situation in our home countries and that I intended to try with all I had to do my part at home. He gave me a most cordial smile and said he would do as much in Russia.”

“Truman believed in personal diplomacy. He believed in personal contacts with people. He prided himself in his ability to understand people and work with them,” Rushay said. “[Stalin] was a guy he felt he can kind of relate to.”

But to say that the two men had chemistry would be overstating the relationship, Leffler said. For one, the United States and the Soviet Union were formal allies against great adversaries and were working together to end the war. As Leffler wrote in his book, American leaders were willing to gloss over the Soviet leader’s history of barbarism because they had “great hope” for Stalin in 1945 to help defeat Japan.

“Stalin might be insulting at times, but he could be dealt with because he seemed responsive to American power and capable of demonstrating some self-restraint on the Soviet periphery,” Leffler wrote. “What went on in Russia, Truman declared, was the Russians’ business. The president was fighting for U.S. interests, and Uncle Joe seemed to be the man with whom one could deal.”

Behind the scenes, however, policymakers were starting to consider whether they really wanted Stalin and the Soviet Union’s participation, Leffler said. Truman and his secretary of state, James Byrnes, began to think that if the United States dropped the atomic bomb, Japan would surrender and there would be no need for the Soviet Union to intervene.

Just days after the conference ended in August 1945, the United States dropped the first combat atomic bomb, “Little Boy,” incinerating much of the Japanese city of Hiroshima. A second one obliterated the city of Nagasaki shortly after.

Two years later, in 1947, the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States began. But Truman’s opinion of Stalin didn’t seem to change.

“I got very well acquainted with Joe Stalin, and I like old Joe! He is a decent fellow. But Joe is a prisoner of the Politburo,” Truman said in Oregon in 1948, referring to the Soviet Union’s policymaking body.”

No comments:

Post a Comment