.

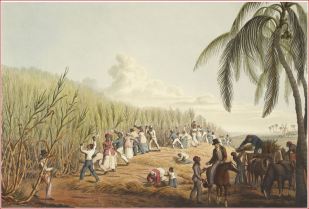

“A secret colonial memo from 1919...showed that the British government realised that everything had changed, too: “Nothing we can do will alter the fact that the black man has begun to think and feel himself as good as the white.”...Kitchener’s private attitude was that black soldiers should never be allowed at the front alongside white soldiers.”…Filled with boatloads of African slaves, “Caribbean islands became the hub of the British Empire. The sugar colonies were Britain’s most valuable colonies.”…Below, “Enslaved people cutting sugarcane on the Caribbean island of Antigua, aquatint from Ten Views of the Island of Antigua by William Clark, 1832. The British Library (Public Domain)”

11/6/2002, “‘There were no parades for us’,” UK Guardian, Simon Rogers

“More than four million men and women from Britain’s colonies volunteered for service during the first and second world wars. Thousands died, thousands went missing in action, and many more were wounded or spent years as PoWs. But until now their sacrifice has been largely ignored by the mother country they fought to protect….

The World War I “veteran, George Blackman, age 105, 4th Battalion, British West Indies Regiment, 1914-1919:

The World War I “veteran, George Blackman, age 105, 4th Battalion, British West Indies Regiment, 1914-1919:

George Blackman leaps up, brandishing his walking stick. “Like this,” he breathes, imitating the thrust of a bayonet. “Like that,” he says, mimicking the butt of the rifle. “I still got the action. I’m old now, but I still got the action.”

George is 105. When he was born in Barbados in 1897, Queen Victoria was on the throne and two-thirds of the world was coloured pink.

He points to a scar above his left eyebrow. “That is a bayonet cut on the eye.” He touches his hands. “This is from the blow of the rifle butt.”

[Recruits in Jamaica 1916 © IWM (Q 52423)]

[Black men living in Britain in 1914 wishing to fight for Britain’s King in WWI joined the black Caribbean British West Indies Regiment as “they had found that racial prejudices of the day usually made it hard for them to join white British regiments.”]

George is almost certainly the last man alive of the force of 15,000 who rushed from the beauty of the Caribbean to the mud and gore of Flanders and the Somme to defend king and country during the first world war. His old comrades are all gone now – the last, Jamaican soldier Eugent Clarke, died earlier this year at 108. When Blackman goes, that will be it.

Sitting in his niece’s house in northern Barbados, Blackman

is now partially blind and almost deaf. Anita tidies his shirt collar

for him as we speak. He is still articulate and energetic, and his fiercest remarks are reserved for England. “I need help but the English government don’t help me with nothing,“ he says. “It’s she, she who give me this,” he says, gesturing to Anita.

Sitting in his niece’s house in northern Barbados, Blackman

is now partially blind and almost deaf. Anita tidies his shirt collar

for him as we speak. He is still articulate and energetic, and his fiercest remarks are reserved for England. “I need help but the English government don’t help me with nothing,“ he says. “It’s she, she who give me this,” he says, gesturing to Anita.

This bitterness has been growing deeper over the years. There was a time when he would have done anything for the mother country. In 1914, in a flush of youth and patriotism, he told the recruiting officer he was 18 – he was actually 17 – and joined the British West Indies Regiment. “Lord Kitchener said with the black race, he could whip the world. We sang songs, ‘Run Kaiser William, run for your life, boy’.” He closes his eyes as he sings, and then keeps them closed for the rest of our interview.

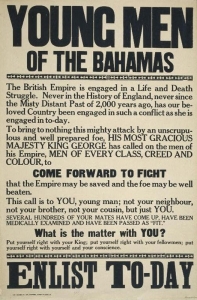

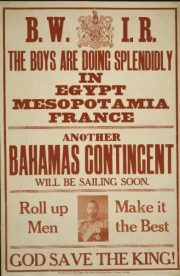

“We wanted to go. Because the island government told us that the king said all Englishmen must go to join the war. The country called all of us.”

Enthusiasm for the battle was widespread across the Caribbean. While some declared it a white man’s war, leaders and thinkers such as the Jamaican Marcus Garvey said that young men from the islands should fight with the British in order to prove their loyalty and to be treated as equals.The islands donated £60m in today’s money to the war effort – cash they could ill afford.

Enthusiasm for the battle was widespread across the Caribbean. While some declared it a white man’s war, leaders and thinkers such as the Jamaican Marcus Garvey said that young men from the islands should fight with the British in order to prove their loyalty and to be treated as equals.The islands donated £60m in today’s money to the war effort – cash they could ill afford.

While Kitchener’s private attitude was that black soldiers should never be allowed at the front alongside white soldiers, the enormous losses-and the interference of King George V-made it inevitable. Although Indian soldiers had been briefly in the trenches in 1914 and 1915, Caribbean troops did not arrive until 1915.

The journey to Europe was perilous-–hundreds of soldiers from Jamaica succumbed to severe frostbite when their troopship was diverted via Halifax in Canada. Their winter uniforms were left locked up while they froze in thin summer clothes.

When they arrived, they often found that fighting was to be done by white soldiers only– black soldiers were assigned the dirty and dangerous jobs of loading ammunition, laying telephone wires and digging trenches. Conditions were appalling. Blackman rolls up his sleeve to show me his armpit. “It was cold. And everywhere there were white lice. We had to shave the hair there because the lice grow there. All our socks were full of white lice.”…

Yet

there is evidence that some Caribbean soldiers were involved in actual

combat in France. Photographs from the time show black soldiers armed

with British Lee Enfield rifles, while there are reports of West

Indies Regiment soldiers fighting off counter-attacks – one account

tells how a group fought off a German assault armed only with knives they had brought from home. Blackman – who was born to a white mother from London and a Barbadian black father – still remembers trench fights he fought in, alongside white soldiers. “They called us darkies,“ he says, recalling the casual racism of the time. “But

when the battle starts, it didn’t make a difference. We were all the

same. When you’re there, you don’t care about anything. Every man there

is under the rifle.”

Yet

there is evidence that some Caribbean soldiers were involved in actual

combat in France. Photographs from the time show black soldiers armed

with British Lee Enfield rifles, while there are reports of West

Indies Regiment soldiers fighting off counter-attacks – one account

tells how a group fought off a German assault armed only with knives they had brought from home. Blackman – who was born to a white mother from London and a Barbadian black father – still remembers trench fights he fought in, alongside white soldiers. “They called us darkies,“ he says, recalling the casual racism of the time. “But

when the battle starts, it didn’t make a difference. We were all the

same. When you’re there, you don’t care about anything. Every man there

is under the rifle.”

[Screen shot, @9:42, British West Indies Regiment black soldiers marching in Palestine in 1917. These men were often workers on British Caribbean plantations and would be sent back to the plantations after WWI. Service in the British military didn’t change their status. Imperial War Museum]

He remembers one attack with particular clarity. “The Tommies [soldiers] said, ‘Darkie, let them have it.‘ I made the order: ‘Bayonets, fix,’ and then ‘B company, fire.’ You know what it is to go and fight somebody hand to hand? You need plenty nerves. They come at you with the bayonet. He pushes at me, I push at he. You push that bayonet in there and hit with the butt of the gun – if he is dead he is dead, if he live he live.”

The West Indies Regiment experienced racism from the Germans as well as the British. “The Tommies, they brought up some German prisoners and these prisoners were spitting on their hands and wiping on their faces, to say we were painted black,” says Blackman.

He didn’t make friends. “Don’t have no friend. A soldier don’t got friends. Know why? You believe that you are dead now. Your friend is this: the gun. That is your friend.”

At the end of the war, after years of hard fighting, not only against the Germans but also the Turks, men of the West Indies Regiment were transferred to a British army base in Taranto, Italy,where one of the bitterest events of the war would occur-a mutiny. Days were tough there and comprised largely of manual labour such as loading ammunition, or even cleaning clothes and latrines for British soldiers. Blackman, who was not there long, remembers it being hard. “From Marseille, it was seven days to reach Taranto. It is a seaport – all the boats were coming from London with ammunition. We have to unload the boat, the train come and we got to load the train to take the ammunition up the line.”

For some of the black troops there, a pay rise for the white soldiers-but not them-was the final indignity. Riots ensued and senior British officers were assaulted. Eventually the mutiny was put down, with one soldier executed and several others given lengthy jail sentences. But the black soldiers were left with a new-found feeling of rebellion. [In the US, “Congress passed a bill authorizing equal pay for Black and white soldiers in 1864.“]

The immediate result was that the West Indies troops were kept away from the victory parades that marked the end of the war, and hurried home under armed guard. “When the war finish, there was nothing,” says Blackman. “I had to come and look for work. The only thing that we had is the clothes and the uniform that we got on. The pants, the jacket and the shirt and the boots. You can’t come home naked.

“When we got home, if you got a mother or father you have something, but if you’re alone, you got to look for work. When I come I had nobody. I had to look for work. I had to eat and buy clothes.Who going to give me clothes? I didn’t have a father or nobody. Now I said, ‘The English are no good.’ I went to Jamaica and I meet up some soldiers and I asked them, ‘Here boy, what the government give you?’ They said, ‘The government give us nothing.‘ I said, ‘We just the same.'”

And that’s when Blackman disappeared off the veterans’ radar. Travelling around South America, he worked as a mechanic in Colombia, before retiring to Venezuela to live with his daughter until the Barbados government helped to bring him home earlier this year [2002].

As a Barbadian living in Venezuela for decades, he was not entitled to a pension there. The Barbados government (in the form of one dedicated civil servant) is still processing his application for one in his home country. And from the British? Nothing.

The empire changed when Blackman and his comrades returned from France. The soldiers who emerged were so politicised that island governments encouraged them to emigrate to Cuba, Colombia and Venezuela. Those who returned to their countries altered everything. Gunner Norman Manley, who had seen his brother blown apart in front of him during the war, eventually took Jamaica to independence [from the British Empire], becoming its first prime minister in 1962.

A secret colonial memo from 1919, uncovered by researchers for a Channel 4 programme on the Taranto mutiny, showed that the British government realised that everything had changed, too:

“Nothing we can do will alter the fact that the black man has begun to think and feel himself as good as the white.“ In a sense, history was rewritten. That meant no celebrations, no official acknowledgment.

For George Blackman, the situation has become even more simple. “England don’t have anything to do with me now. England turned me over.” He opens his eyes – they are almost blue. “Barbadians rule Barbados now.””…[Images above from “The West Indian experience” added by blog editor]

……………………………………………

Added: BBC article: After World War I, UK whites were violently opposed to the presence of blacks in their country: “Because of the large-scale onslaughts on blacks, and in an attempt to appease the British public, the government decided to repatriate as many blacks as they could and by the middle of September 1919, about 600 had been repatriated.”

3/10/2011, “A White Man’s War? World War One and the West Indies," BBC, Glenford D. Howe

“The colonies join the war effort”

“By the outbreak of war in 1914, centuries of alienation and the suppression of the remnants of African cultural practices, and the proliferation of British institutions, culture and language, had created staunchly loyal Black Britishers in Barbados and other colonies. The expression of support for Britain from the West Indian population was therefore, not surprisingly, quite overwhelming.”…

“By the outbreak of war in 1914, centuries of alienation and the suppression of the remnants of African cultural practices, and the proliferation of British institutions, culture and language, had created staunchly loyal Black Britishers in Barbados and other colonies. The expression of support for Britain from the West Indian population was therefore, not surprisingly, quite overwhelming.”…

Subhead, “Should blacks participate?”…

“Although the British officials were not keen on having blacks serve on the Western Front, the extent of the West Indian agitation, and devastating losses suffered by the Allies, eventually forced the British government to approve the formation of West Indian contingents and their service overseas.”…

Subhead, “Recruitment and Return“…

“By the middle of 1916, men rejected in England as unfit or as invalid had begun to return to the West Indies.…Having relinquished their jobs to fight for King and Country these men were left to experience destitution and poverty.”…

Subhead, “The Halifax Incident”

“The spectacle of returning invalids had a sobering effect on potential recruits. The sight of men hobbling on sticks and crutches was evident in Grenada, and there were in Trinidad, according to The West Indian Gazette, ‘many pathetic scenes to be witnessed‘. In Jamaica, however, it was the catastrophic journey of their third contingent that dramatically brought home the possible dangers which awaited potential recruits.

On 6 March 1916 the third Jamaica contingent, comprising 25 officers and 1,115 other ranks, departed for England on board the ship Verdala. Due to enemy submarine activity in the region, the Admiralty ordered the ship to make a diversion to Halifax – but before it could reach its destination it encountered a blizzard. Since the Verdala was not adequately heated and the black soldiers had not been properly equipped with warm clothing, substantial casualties resulted: approximately 600 men suffered from exposure and frostbite and there were five immediate deaths….

Conscription measures were eventually passed in Jamaica and other colonies in order to recruit more men, especially those of quality, but these measures were never enforced. The men who arrived overseas from the region to serve in the British West Indian Regiment (BWIR) were therefore all volunteers even though, as elsewhere in the empire, some joined because of economic, legal and private pressures.”…

Subhead, “Discrimination at war”

“Even though there was a high degree of standardisation and regularisation in the disciplinary code structure of the army, inequalities in attitudes towards and treatment of the different races, classes and ethnic groups did exist. Major problems of discrimination were to be found in the practical application of army regulations in an environment in which stereotypes of race and class were prevalent….Adjustment into army life was usually more difficult and precarious for the black soldier than for his white counterpart because of racism. One veteran, Sir Etienne Dupuch, wrote of the ‘consciousness of discrimination’ against ‘native troops’ which blacks felt in the army.

One response adopted by the black soldiers was to write to local newspapers urging for ‘something hot’ to be written against race prejudice. Their intention was to mobilise West Indian public opinion in the hope of getting proper representation and possibly relief from the daily harassment.“…

Subhead, “Mutiny at Taranto”

“After Armistice Day, on 11 November 1918, the eight BWIR battalions in France and Italy were concentrated at Taranto in Italy to prepare for demobilisation. They were subsequently joined by the three battalions from Egypt and the men from Mesopotamia [Iraq]. As a result of severe labour shortages at Taranto, the West Indians had to assist with loading and unloading ships and do labour fatigues. This led to much resentment, and on 6 December 1918 the men of the 9th Battalion revolted and attacked their officers. On the same day, 180 sergeants forwarded a petition to the Secretary of State complaining about the pay issue, the failure to increase their separation allowance [as had been done for white soldiers], and the fact that they had been discriminated against in the area of promotions.

[BBC says: “As a result of severe labour shortages at Taranto, the West Indians had to assist with loading and unloading ships and do labour fatigues.”…You don’t explain why “severe labour shortages” didn’t also require white soldiers to clean latrines.]

During the mutiny, which lasted about four days, a black NCO shot and killed one of the mutineers in self-defence and there was also a bombing. Disaffection spread quickly among the other soldiers and on 9 December the ‘increasingly truculent’ 10th Battalion refused to work. A senior commander, Lieutenant Colonel Willis, who had ordered some BWIR men to clean the latrines of the Italian Labour Corps, was also subsequently assaulted. In response to calls for help from the commanders at Taranto, a machine-gun company and a battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment were despatched to restore order. The 9th BWIR was disbanded and the men distributed to the other battalions which were all subsequently disarmed. Approximately 60 soldiers were later tried for mutiny and those convicted received sentences ranging from three to five years, but one man got 20 years, while another was executed by firing squad.

Although the mutiny was crushed, the bitterness persisted, and on 17 December about 60 NCOs held a meeting to discuss the question of black rights, self-determination and closer union in the West Indies. An organisation called the Caribbean League was formed at the gathering to further these objectives. At another meeting on 20 December, under the chairmanship of one Sergeant Baxter, who had just been superseded by a white NCO, a sergeant of the 3rd BWIR argued that the black man should have freedom and govern himself in the West Indies and that if necessary, force and bloodshed should be used to attain these aims. His sentiments were loudly applauded by the majority of those present. The discussion eventually drifted from matters concerning the West Indies to one of grievances of the black man against the white. The soldiers decided to hold a general strike for higher wages on their return to the West Indies. The headquarters for the Caribbean League was to be in Kingston, Jamaica, with sub-offices in the other colonies.

Meanwhile, the cessation of hostilities quickly led to a profound change in white attitudes to the presence of blacks in the United Kingdom. As white seamen and soldiers were demobilised and the competition for jobs intensified, so too did the level of race and class antagonism, especially in London and the port cities. The more serious aspect of this was the numerous riots which erupted and the assaults on blacks in the United Kingdom. Because of the large-scale onslaughts on blacks, and in an attempt to appease the British public, the government decided to repatriate as many blacks as they could and by the middle of September 1919, about 600 had been repatriated.”

Subhead, “Home Front”

“Even more alarming to the authorities, especially those in the West Indies, was the fact that between 1916 and 1919 a number of colonies including St Lucia, Grenada, Barbados, Antigua, Trinidad, Jamaica and British Guiana experienced a series of strikes in which people were shot and killed. It was into this turmoil that the disgruntled seamen and ex-servicemen were about to return and many people in the region were hoping or anticipating – and, in the case of the authorities, fearing – that their arrival would bring the conflict to head.

When the disgruntled BWIR soldiers began arriving back in the West Indies they quickly joined a wave of worker protests resulting from a severe economic crisis produced by the war, and the influence of black nationalist ideology espoused by black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey and others. Disenchanted soldiers and angry workers unleashed a series of protest actions and riots in a number of territories including Jamaica, Grenada and especially in British Honduras [now known as Belize].

West Indian participation in the war was a significant event in the still ongoing process of identity formation in the post-emancipation era of West Indian history. The war stimulated profound socio-economic, political and psychological change and greatly facilitated protest against the oppressive conditions in the colonies, and against colonial rule by giving a fillip to the adoption of the nationalist ideologies of Marcus Garvey and others, throughout the region. The war also laid the foundation for the nationalist upheavals of the 1930s in which World War One veterans were to play a significant role.”

West Indian participation in the war was a significant event in the still ongoing process of identity formation in the post-emancipation era of West Indian history. The war stimulated profound socio-economic, political and psychological change and greatly facilitated protest against the oppressive conditions in the colonies, and against colonial rule by giving a fillip to the adoption of the nationalist ideologies of Marcus Garvey and others, throughout the region. The war also laid the foundation for the nationalist upheavals of the 1930s in which World War One veterans were to play a significant role.”

………………………………

Added: Belize “has retained its historical link with the United Kingdom through membership in the Commonwealth.”

“Belize, which was known as British Honduras until 1973, was the last British colony on the American mainland. Its prolonged path to independence was marked by a unique international campaign (even while it was still a British colony) against the irredentist claims of its neighbour Guatemala. Belize achieved independence on September 21, 1981, but it has retained its historical link with the United Kingdom through membership in the Commonwealth.”

“Belize, which was known as British Honduras until 1973, was the last British colony on the American mainland. Its prolonged path to independence was marked by a unique international campaign (even while it was still a British colony) against the irredentist claims of its neighbour Guatemala. Belize achieved independence on September 21, 1981, but it has retained its historical link with the United Kingdom through membership in the Commonwealth.”

………………..

“About the author: Dr Glenford D Howe is a graduate of and a Research Officer at the Cave Hill campus of the University of the West Indies in Barbados. He is also a graduate of the University of London and a Commonwealth scholar. He has edited and authored several books including The Caribbean Aids Epidemic, Higher Education in the Caribbean and The Empowering Impulse. His forthcoming book on West Indians in World War One will be published by Ian Randle publishers.”

No comments:

Post a Comment