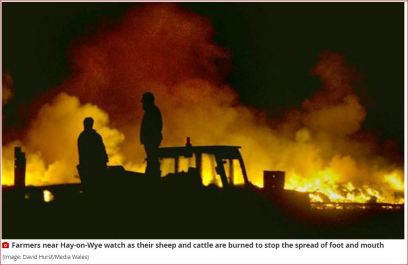

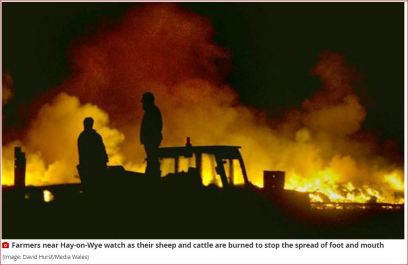

Armchair epidemiologist's 2001 slaughter of millions of healthy animals was sold in same febrile atmosphere in which his 2020 call to imprison healthy families in their homes indefinitely was sold-UK Telegraph, 3/28/20

.

Neil Ferguson himself believes in and practices "herd immunity"–the opposite of “lockdown” theory: “I acted in the belief that I was immune having tested positive for coronavirus and completely isolated myself for almost two weeks after developing symptoms.” BBC, 5/6/20,.…“Despite Prof. Ferguson’s comments [that he had acquired immunity to the virus], it is currently unclear whether people who have recovered from the virus will be immune or able to catch it again.”…Ferguson has the greatest “immunity” on earth: He’s tops with the Queen. She awarded him an OBE for his 2001 computer models urgently calling for slaughter of millions of healthy animals.

Two images above, April 12, 2020, “The full horrifying scale of the 2001 foot and mouth outbreak told by the Welsh farmers in the middle of it,“ walesonline.co.uk, Anna Lewis

Two images above, April 12, 2020, “The full horrifying scale of the 2001 foot and mouth outbreak told by the Welsh farmers in the middle of it,“ walesonline.co.uk, Anna Lewis

Image above, April 13, 2001, “Scientists back rapid slaughter policy,” BBC, “No alternative this time around, say scientists.”

Image above, April 13, 2001, “Scientists back rapid slaughter policy,” BBC, “No alternative this time around, say scientists.”

Image above, May 30, 2001, “100 days of Foot and Mouth,” BBC

Image above, 4/4/2001, “Animal disposal row intensifies,” BBC…[As someone recently said, “This time we’re the cattle.”]

…………………………………….. “The scientist whose calculations about the potentially devastating impact of the coronavirus directly led to the countrywide lockdown has been criticised in the past for flawed research. Professor Neil Ferguson, of the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis at Imperial College in London, produced a paper predicting that Britain was on course to lose 250,000 people during the coronavirus epidemic unless stringent measures were taken. His research is said to have convinced Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his advisors to introduce the lockdown. He was behind disputed research that sparked the mass culling of farm animals during the 2001 epidemic of foot and mouth disease, a crisis which cost the country billions of pounds. And separately he also predicted that up to 150,000 people could die from bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, or ‘mad cow disease’) and its equivalent in sheep if it made the leap to humans. To date there have been fewer than 200 deaths from the human form of BSE and none resulting from sheep to human transmission. Mr Ferguson’s foot and mouth disease (FMD) research has been the focus of two highly critical academic papers [one in 2006 and one in 2011peer reviewed in Science] which identified allegedly problematic assumptions in his mathematical modelling.”… [From 2006 Abstract, Kitching, Thrusfield and Taylor: “During the 2001 epidemic of FMD in the United Kingdom (UK), this approach [killing infected animals] was supplemented by a culling policy driven by unvalidated predictive models. The epidemic and its control resulted in the death of approximately ten million animals, public disgust with the magnitude of the slaughter, and political resolve to adopt alternative options, notably including vaccination, to control any future epidemics. The UK experience provides a salutary warning of how models can be abused in the interests of scientific opportunism."…Page 6: “In fact, the epidemic peak preceded the start of pre-emptive contiguous culling. Significantly, more than two weeks after the epidemic peaked, models failed to identify the time at which the epidemic was under control (86).”…Page 5: “Model-driven control strategies: Early in the 2001 epidemic, policy decisions about the control programme were removed from the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF), now known as the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), and placed with the Cabinet Office Briefing Room (COBR) (also known as COBRA because it was Room A). Campbell and Lee (9) comment that: ‘The incredible state of affairs in which a regulatory problem of livestock rearing and farm economics was thought to require a response by a government apparatus designed to deal with problems more akin to general insurrection has passed with little other than approving comment in the official reports’. (COBR was convened most recently in July 2005, in connection with the terrorist bombings in London.) The COBR was

advised by the Chief Scientific Adviser to the Government, who had

established a ‘Science Group’ to help formulate this advice. The Science Group, which first met on 26 March, was dominated by four teams of modellers. To quote the then current MAFF Chief Scientific Adviser, David Shannon (89): ‘… A formally constituted scientific advisory committee would have looked considerably different’. One team had already, on 21 March, used the media to disseminate its dire predictions to the public on the eventual outcome of the epidemic (the course of which would include a general election), unless its advice was followed. The issue then assumed both technical and political dimensions, with the danger of scientists expressing ‘convictions or opinions which (however scientifically founded) cannot in any way be identified with knowledge in the strict sense which science generally affords this term’ (107). The involvement of modelling with the control programme for the FMD epidemic was not part of the pre-arranged contingency plan, but came about in an ad hoc way….The classification of contiguous premises as dangerous contacts became automatic (i.e. not subject to veterinary assessment) on 29 March (104), (the ‘preemptive contiguous cull’) (100). While such a policy might be practical (if not scientifically justifiable) if only a small number of farms are affected (as in the Republic of Ireland in 2001) (42), implementing this policy for the UK epidemic – in which the disease was spread over a wide geographical area – resulted in the destruction of many healthy animals and logistical problems of carcass disposal.”…Page 6: “‘Their idea was to control the disease by culling in contiguous farms. That is fine if you are sitting in front of a computer screen in London. However, it is different on the ground. A person in London will just see the numbers and will say that they have been taken out. That is why it was carnage by computer’ (9, 84). This graphically exemplifies the isolation and abstraction of ‘armchair epidemiology’, whilst also poignantly highlighting the importance of personal involvement in disease control to gain complete insight into its impact. This concept is already well established in the social sciences….(75)….Page 6: “Modelling and scientific method:” “The disparity between the course of the 2001 epidemic and the model predictions demands an explanation. The numerical output of models has an air of intellectual superiority…while also seeming entirely appropriate in a society where numbers can ‘…reassure by appearing to extend control, precision and knowledge beyond their real limits… wrong numbers, one might add, are worst of all because all numbers pose as true’ (11). Numbers, therefore, may convey an illusion of certainty and security that is not warranted (43); for example, because of the use of whatever numerical data are available, regardless of their relevance and quality (38). A model constitutes a theory, and a predictive model is therefore only a theoretical projection.…The degree of confidence in the 2001 predictive models is therefore low because they were not widely tested, and their conclusions (e.g. that pre-emptive contiguous culling was necessary to control the epidemic) have been refuted. Moreover, there are constraints on testedness in any case, because of the rarity of FMD epidemics, and the genetic plasticity of the organism, which can result in strain variation with consequent changes in the transmission characteristics of the virus. Predicting a chance, long-distance transmission event on the virus-contaminated hands of an unsuspecting stockowner would also be impossible, other than to say it might occur.…Additionally, models generated to assist in the control of a specific epidemic are ‘tactical’ rather than ‘strategic’ (46), and this further limits their testedness.” “Appropriateness of model use in 2001,"…"The 2001 predictive models were constructed in an environment of poor-quality data (e.g. they used out-of-date census data for stock levels), and poor epidemiological knowledge (e.g. the transmission characteristics of the virus strain, and the distribution of the initially infected farms, were unknown). Therefore, their use as predictive tools was inappropriate….Page 9: “The model that Ferguson et al. (31) presented to the Science Group in late March probably had the most influence on early policy decisions (93), specifically, the introduction of the pre-emptive contiguous culling policy. However, this model, and the Keeling et al. model (56) that was used to corroborate it,were assigned parameters that could not help but favour that policy, based on field tracing data that should have been viewed with caution. The models were highly sensitive to the accuracy of this information,in

that these data determined the degree of disease transmission to be

simulated before clinical signs and the distance over which the majority

of transmission took place. Despite the fact that the modellers seemed to be aware of these issues, the models were used as strong support for the implementation of the contiguous cull. The authors of this paper argue that the models were not fit for the purpose of predicting the course of the epidemic and the effects of control measures. The models also remain unvalidated. Their use in predicting the effects of control strategies was therefore imprudent. In retrospect, very little of value was added to the FMD control policy by the use of predictive models. The latter therefore failed the most pragmatic ‘litmus test’: namely, usefulness (40; Hugh-Jones, quoted by 79). The key question for any model is whether decisions made with it are more correct than those made without it (17). However, the consequences of following the recommendations of these models were severe: economically, in terms of cost to the country; socially, in terms of misery and even suicides among those involved in the slaughter programme; and scientifically, in the abuse of predictive models, and their possible ultimate adverse effects on disease control policy in the future (see below).“…Page 12: “Conclusions:” “Epidemics of most infectious diseases are subject to mandatory control for which regulatory legislation has been passed. Governmental involvement in disease control, and controversies surrounding it, have a long history, dating back in the UK to the mid-19th Century, when the relaxation of trade restrictions and ensuing epidemics of FMD, sheep pox and, notably, rinderpest (cattle plague), saw a change in favour of veterinary policing of the country (113). Now, as then, urgent decisions may need to be taken when facts are uncertain (35). Such decisions are based on received scientific wisdom, which may be either central to regulatory mechanisms (the ‘technocratic model’; 107) or subordinate to political considerations (the ‘Weberian decisionist mode’; 106). In either case, the value of the facts must be judged, and scientific experts must be accountable, not only to government ministers but also to other experts. To date, this has not occurred in the context of the 2001 epidemic....The use of models during epidemics should be restricted to monitoring the epidemic and aiding short-term fine

adjustments to strategies. Comparing real behaviour to ‘expected’

(model-generated) behaviour could alert epidemiologists to unexpected

circumstances in the field, which could then be targeted for action. Models may also be useful to carry out limited ‘what-if’ simulations, to assess risks associated with various developments of the epidemic, so that appropriate contingencies could be made in resource planning. During epidemics, models can usefully support the requisition of resources needed for well-tried control measures, by graphically demonstrating (Page 13) the possible development of an epidemic. However, the utility of predictive models as tactical decision support tools is limited by the innate unpredictability of

disease spread between farms. With particular reference to deciding on

the use of ring vaccination, James and Rushton (53) draw the following

conclusion: ‘The progress of an outbreak of FMD is extremely difficult to predict in the early stages of the disease. The course of an outbreak can be critically affected by minor and inherently unpredictable events, such as a single livestock movement.

For this reason, predictive disease models, which depend on statistical

probabilities of transmission, have not met with much success in predicting the spread of FMD from herd to herd, and still less the impact of control measures.”…] (continuing): “The scientist has robustly defended his work, saying that he had worked with limited data and limited time so the models weren’t 100 per cent right – but that the conclusions it reached were valid. Michael Thrusfield, professor of veterinary epidemiology at Edinburgh University, who co-authored both of the critical reports, said that they had been intended as a “cautionary tale” about how mathematical models are sometimes used to predict the spread of disease. He described his sense of “déjà vu” when he read Mr Ferguson’s Imperial College paper on coronavirus, which was published earlier this month [March 2020]. That paper–Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand–warned that if no action were taken to control the coronavirus, around 510,000 people in Britain would lose their lives. It also predicted that approximately 250,000 people could die if the Government’s conservative approach at the time was not changed. The research, which was based on mathematical models, was key in convincing the Prime Minister that “suppression”–and subsequently a lockdown—was the only viable option to avoid huge loss of life and an NHS meltdown. This week [March 2020], a second paper authored by Mr Ferguson and the Imperial team further predicted that 40 million people worldwide could die if the coronavirus outbreak was left unchecked. But scientists warned last night about the dangers in making sweeping political judgments based on mathematical modelling which may be flawed. In 2001, as foot and mouth disease (FMD) broke out in parts of Britain, Ferguson and his team at Imperial College produced predictive modelling – which was later criticised as “not fit for purpose.””… (continuing): “At the time, however, it proved highly influential and helped to persuade Tony Blair’s government to carry out a widespread pre-emptive culling which ultimately led to the deaths of more than six million cattle, sheep and pigs. The cost to the economy was later estimated at £10 billion. The model produced in 2001 by Professor Ferguson and his colleagues at Imperial suggested that the culling of animals include not only those found to be infected with the virus but also those on adjacent farms even if there was no physical evidence of infection. “Extensive culling is sadly the only option for controlling the current British epidemic, and it is essential that

the control measures now in place be maintained as case numbers decline

to ensure eradication,” said their report, published after the cull

began. The strategy of mass slaughter –

known as contiguous culling – sparked revulsion in the British public

and prompted analyses of the methodology which has led to it. A 2011 paper, Destructive Tension: mathematics versus experience – the progress and control of the 2001 foot and mouth epidemic in Great Britain, found that the government ordered the destruction of millions of animals because of “severely flawed” modelling. According to one of its authors – the former head of the Pirbright Laboratory at the Institute for Animal Health, Dr Alex Donaldson – Ferguson’s models made a “serious error” by “ignoring the species composition of farms,” and the fact that the disease spread faster between some species than others. The report stated: “The mathematical models were, at best, crude estimations that could not differentiate risk between farms and, at worst, inaccurate representations of the epidemiology of FMD.” (continuing): “The paper said that “the models were not fit for the purpose of predicting the course of the epidemic and the effects of control measures. The models also remain unvalidated. Their use in predicting the effects of control strategies was therefore imprudent.” “This is déjà vu. During the [2001] [FMD] epidemic there was quite vocal opposition from members of the vet profession – especially those who had their hands soaked in blood, killing perfectly healthy cattle. Last night, Dr Paul Kitching – lead author of Use and abuse of mathematical models, and the former chief veterinarian of Canada’s British Columbia province – raised fears over the modelling being done on coronavirus. “The basic principles on modelling described in our paper apply to this Covid-19 crisis as much as they did to the FMD outbreak. “In view of the low numbers of Covid-19 tests being reported as carried out in affected countries, it is difficult to understand what informs the current models. In particular the transmission rate. How many mild and subclinical infections are occurring?” “The model driven policy of FMD control resulted in tragedy. Vast numbers of animals were slaughtered without reason. Untold human and animal suffering was the result–not to mention the financial consequences.” However, Sir David King, who was the Chief Scientific Advisor to the

government in 2001, said that criticism of the epidemiological modelling

was “misplaced.” He said: “I would agree there was some unnecessary culling taking

place, but this is simply because there wasn’t a unity in the way the

thing was being handled.” Professor Ferguson said of his modelling for FMD: “A number of

factors going into deciding policy, of which science – particularly

modelling – is only one. It is ludicrous to say now that our model changed government policy. A number of factors did.”… (continuing): ““We were doing modelling in real time as the other groups were in 2001 – certainly the models weren’t 100% right, certainly with limited data and limited time to do the work. But I think the broad conclusions reached were still valid.” Of his work on BSE, in which he predicted human death toll of between

50 and 150,000, Professor Ferguson said: “Yes, the range is wide, but

it didn’t actually lead to any change in government policy.” Others have directly criticised the methodology employed by Ferguson and his team in their coronavirus study. John Ioannidis, professor in disease prevention at Stanford University, said: “The Imperial College study has been done by a highly competent team of modellers. However, some of the major assumptions and estimates that are built in the calculations seem to be substantially inflated.”… He [Ferguson] defended the conclusions reached “in terms of the overwhelming demand on healthcare systems imposed by this [corona] virus.””…

……………………………………..

Added: 2011 peer reviewed study disagreed with Ferguson’s 2001 modeling and preemptive slaughter.

May 6, 2011, “Mass culling for foot-and-mouth ‘may be unnecessary‘,” BBC News, By Pallab Ghosh, Science correspondent

“The mass cull of farm animals to control the spread of foot-and-mouth disease may be unnecessary if there is a new outbreak, scientists suggest.

A new analysis of disease transmission suggests that future outbreaks might be controlled by early detection and killing only affected animals….

The research, by a UK team,is reported in the journal Science.”…

[2011 “Abstract: Control of many infectious diseases relies on the detection of clinical cases and the isolation, removal, or treatment of cases and their contacts. The success of such “reactive” strategies is influenced by the fraction of transmission occurring before signs appear.We performed experimental studies of foot-and-mouth disease transmission in cattle and estimated this

fraction at less than half the value expected from detecting virus in

body fluids, the standard proxy measure of infectiousness. This is because the infectious period is shorter (mean 1.7 days) than currently realized, and animals are not infectious until, on average, 0.5 days after clinical signs appear. These results imply that controversial preemptive [slaughter] control measures may be unnecessary; instead, efforts should be directed at early detection of infection and rapid intervention.” May 6, 2011, “Relationship Between Clinical Signs and Transmission of an Infectious Disease and the Implications for Control,“ Science]

(continuing, BBC): “Until now, vets had assumed animals could be infectious while they carried the virus that causes foot-and-mouth, which may be for between four and eight days.

However, by exposing calves to infected cattle and closely monitoring them, researchers from the Institute for Animal Health in Surrey and Edinburgh University discovered that the period of infection was less than two days.

Perhaps more importantly, the researchers also discovered that animals were not infectious until they showed symptoms of the disease.…

The research also suggests that vets should not be wary of using vaccination to control any future outbreak, as they were in 2001.

Then, there was concern that vaccination would lead to animals becoming infected at a very low level without displaying symptoms, and that these animals could in turn have infected animals in other farms.”

The new research, however, suggests that this kind of subclinical infection is not a worry.

It indicates that if an animal does not show symptoms, it is not infectious; so vaccinating in the face of an outbreak might be more effective than scientists previously thought.”

……………………………………..

Added: As of June 2, 2020. Neil Ferguson remains a top Covid-19 advisor to the UK government including the House of Lords:

June 2, 2020, “‘Prof Lockdown’ Neil Ferguson [of London’s Imperial College] admits Sweden used same science as UK [but not the same tough restrictions],” UK Telegraph, Henry Bodkin, Health and Science correspondent

“Lockdowns are crude.

Lockdown is a blunt instrument and, when possible, should be replaced with more precise measures that cause less economic damage, the epidemiologist said.…

“Lockdowns are very crude policies and what we’d like to do is have much more targeted controlled transmission going forward,” he said….

He revealed that the issue of lockdown fatigue was not something his team had taken into account.

“I think the issue of fatigue was not something we ever modelled, some people had that view on Sage but it wasn’t one I shared or other modellers looked at,” he told the committee….

In comments that appear to support the current gradual easing of restrictions, Prof Ferguson said: “I suspect though, under any scenario that levels of transmission and numbers of cases will remain relatively flat between now and September, short of very big policy changes or behaviour changes in the community….

Contact tracing

The Government’s new track and trace programme will not on its own solve the crisis, Professor Ferguson believes.

“It’s not a panacea,” he said, predicting that the scheme would reduce the R value by 0.25 at the most.

“It depends on not just what proportion of people show symptoms but

then what proportion of people can actually identify contacts or portion

contacts identified, and then how quickly they’re identified,” he

said.”

………………..

...........

No comments:

Post a Comment