Posted 2/1/2015 on You Tube, “Obama Openly Admits ‘Brokering Power Transition’ In Ukraine“…(in linked clip, relevant Obama statements play twice) Obama also says Putin’s “decision around Crimea” wasn’t because of “some grand strategy:”

Text from Obama interview with CNN’s Fareed Zakaria

Obama: “And since Mr. Putin made this decision around Crimea and Ukraine not because of some grand strategy, but essentially because he was caught off balance by the protests in the Maidan [Kiev] and Yanukovych then fleeing after we had brokered a deal to transition power [overthrow elected government] in Ukraine.”

……………………

Added:

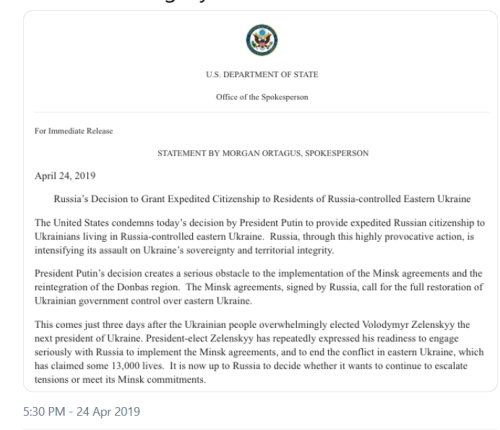

Above, 4/24/19, US State Dept. Spox, Morgan Ortagus

......

Above, 4/24/19, US State Dept. Spox, Morgan Ortagus

…………………………..

Ukraine’s only problem is the US which since 1991 has insisted on ruling it as colony:

Above, 4/25/19, Roman Zubkov twitter

Above, 4/25/19, UK Geol twitter

Above, 4/25/19, Serbian Patriot twitter

Above, 4/25/19, Odd lots twitter

Above, 4/25/19, Serbian Patriot twitter

Above, 4/25/19, Serbian Patriot twitter

Above, 4/25/19, Odd lots twitter

……………………………………….

Added: Two articles, 2014 and 2015, about Ukraine misinformation: “The most disturbing novelty of the Ukrainian crisis is the way Putin and other Russian leaders are routinely demonised. At the height of the cold war when the dispute between Moscow and the west was far more dangerous, backed as it was by the danger of nuclear catastrophe, Brezhnev and Andropov were never treated to such public insults by western commentators and politicians.“…Nor does US insult openly Communist leaders of great, big Communist China. After Soviet Union ended in 1991, US elites thought Russia was theirs for the taking, “ours to lose,” and with Yeltsin US elites plundered it as if it were a rag doll, even ran Yeltsin’s 1996 presidential campaign (“Yanks to the Rescue,” Time, 7/15/1996). Now US personnel believe Russia must be broken up and distributed to other countries, and recommend that US “should promote regional and ethnic self-determination inside the Russian Federation….NATO should prepare contingencies for both the dangers and the opportunities that Russia’s fragmentation will present. In particular, Moscow’s European neighbors must be provided with sufficient security [ie, US taxpayer funded heavy weapons] to shield themselves from the most destabilizing scenarios while preparations are made for engaging with emerging post-Russia entities...” Meaning,“the West should actively stoke longstanding regional and ethnic tensions with the ultimate aim of a dissolution of the Russian Federation.” US is totally focused on global aggression: In 70+ years, the “US military” hasn’t defended the US “homeland:” “For the last 70 years, the obsession of US strategists has not been to defend their people, but to maintain their military superiority over the rest of the world." (Meyssan, 8/22/2017)

2014 article:

“After Crimeans voted overwhelmingly to join Russia, the bulk of the western media abandoned any hint of even-handed coverage.”

4/30/2014, “It’s not Russia that’s pushed Ukraine to the brink of war,” UK Guardian, Seumas Milne, “The attempt to lever Kiev into the western camp by [US] ousting an elected leader made conflict. It could be a threat to us all.”

“The threat of war in Ukraine is growing. As the unelected government in Kiev declares itself unable to control the rebellion in the country’s east, John Kerry brands Russia a rogue state. The US and the European Union step up sanctions against the Kremlin accusing it of destabilising Ukraine. The White House is reported to be set on a new cold war policy with the aim of turning Russia into a “pariah state”.

That might be more explicable if what is going on in eastern Ukraine now were not the mirror image of what took place in Kiev a couple of months ago. Then, it was armed protesters in Maidan Square seizing government buildings and demanding a change of government and constitution. US and European leaders championed the “masked militants” and denounced the elected government for its crackdown, just as they now back the unelected government’s use of force against rebels occupying police stations and town halls in cities such as Slavyansk and Donetsk.

“America is with you,” Senator John McCain told demonstrators then, standing shoulder to shoulder with the leader of the far-right Svoboda party as the US ambassador haggled with the state department over who would make up the new Ukrainian government.

When the Ukrainian president was replaced by a US-selected administration, in an entirely unconstitutional takeover, politicians such as William Hague brazenly misled parliament about the legality of what had taken place: the imposition of a pro-western government on Russia’s most neuralgic and politically divided neighbour.

Putin bit back, taking a leaf out of the US street-protest playbook – even though, as in Kiev, the protests that spread from Crimea to eastern Ukraine evidently have mass support. But what had been a glorious cry for freedom in Kiev became infiltration and insatiable aggression in Sevastopol and Luhansk.

After Crimeans voted overwhelmingly to join Russia, the bulk of the western media abandoned any hint of even-handed coverage. So Putin is now routinely compared to Hitler, while the role of the fascistic right on the streets and in the new Ukrainian regime has been airbrushed out of most reporting as Putinist propaganda.

So you don’t hear much about the Ukrainian government’s veneration of wartime Nazi collaborators and pogromists, or the arson attacks on the homes and offices of elected communist leaders, or the integration of the extreme Right Sector into the national guard, while the anti-semitism and white supremacism of the government’s ultra-nationalists is assiduously played down, and false identifications of Russian special forces are relayed as fact.

The reality is that, after two decades of eastward Nato expansion, this crisis was triggered by the west’s attempt to pull Ukraine decisively into its orbit and defence structure, via an explicitly anti-Moscow EU association agreement. Its rejection led to the Maidan protests and the installation of an anti-Russian administration – rejected by half the country – that went on to sign the EU and International Monetary Fund agreements regardless.

No Russian government could have acquiesced in such a threat from territory that was at the heart of both Russia and the Soviet Union. Putin’s absorption of Crimea and support for the rebellion in eastern Ukraine is clearly defensive, and the red line now drawn: the east of Ukraine, at least, is not going to be swallowed up by Nato or the EU.

But the dangers are also multiplying. Ukraine has shown itself to be barely a functioning state: the former government was unable to clear Maidan, and the western-backed regime is “helpless” against the protests in the Soviet-nostalgic industrial east. For all the talk about the paramilitary “green men” (who turn out to be overwhelmingly Ukrainian), the rebellion also has strong social and democratic demands: who would argue against a referendum on autonomy and elected governors?

Meanwhile, the US and its European allies impose sanctions and dictate terms to Russia and its proteges in Kiev, encouraging the military crackdown on protesters after visits from Joe Biden and the CIA director, John Brennan. [CIA’s John Brennan?] But by what right is the US involved at all, incorporating under its strategic umbrella a state that has never been a member of Nato, and whose last elected government came to power on a platform of explicit neutrality? It has none, of course – which is why the Ukraine crisis is seen in such a different light across most of the world. There may be few global takers for Putin’s oligarchic conservatism and nationalism, but Russia’s counterweight to US imperial expansion is welcomed, from China to Brazil.

In fact, one outcome of the crisis is likely to be a closer alliance between China and Russia, as the US continues its anti-Chinese “pivot” to Asia. And despite growing violence, the cost in lives of Russia’s arms-length involvement in Ukraine has so far been minimal compared with any significant western intervention you care to think of for decades.

The risk of civil war is nevertheless growing, and with it the chances of outside powers being drawn into the conflict. Barack Obama has already sent token forces to eastern Europe and is under pressure, both from Republicans and Nato hawks such as Poland, to send many more. Both US and British troops are due to take part in Nato military exercises in Ukraine this summer.

The US and EU have already overplayed their hand in Ukraine. Neither Russia nor the western powers may want to intervene directly, and the Ukrainian prime minister’s conjuring up of a third world war presumably isn’t authorised by his Washington sponsors. But a century after 1914, the risk of unintended consequences should be obvious enough – as the threat of a return of big-power conflict grows. Pressure for a negotiated end to the crisis is essential.

………………………………………..

2015 article:

2/19/2015, “Frontline Ukraine: Crisis in the Borderlands by Richard Sakwa review – an unrivalled account,“ UK Guardian, Jonathan Steele

“At last, a balanced assessment of the Ukrainian conflict – the problems go far beyond Vladimir Putin."

“When Arseniy Yatsenyuk, Ukraine’s prime minister, told a German TV station recently that the Soviet Union invaded Germany, was this just blind ignorance? Or a kind of perverted wishful thinking? If the USSR really was the aggressor in 1941, it would suit Yatsenyuk’s narrative of current geopolitics in which Russia is once again the only side that merits blame.

When Grzegorz Schetyna, Poland’s deputy foreign minister, said Ukrainians liberated Auschwitz, did he not know that the Red Army was a multinational force in which Ukrainians certainly played a role but the bulk of the troops were Russian? Or was he looking for a new way to provoke the Kremlin?

Faced with these irresponsible distortions, and they are replicated in a hundred other prejudiced comments about Russian behaviour from western politicians as well as their eastern European colleagues, it is a relief to find a book on the Ukrainian conflict that is cool, balanced, and well sourced. Richard Sakwa makes repeated criticisms of Russian tactics and strategy, but he avoids lazy Putin-bashing and locates the origins of the Ukrainian conflict in a quarter-century of mistakes since the cold war ended. In his view, three long-simmering crises have boiled over to produce the violence that is engulfing eastern Ukraine. The first is the tension between two different models of Ukrainian statehood. One is what he calls the “monist” view, which asserts that the country is an autochthonous cultural and political unity and that the challenge of independence since 1991 has been to strengthen the Ukrainian language, repudiate the tsarist and Soviet imperial legacies, reduce the political weight of Russian-speakers and move the country away from Russia towards “Europe”. The alternative “pluralist” view emphasises the different historical and cultural experiences of Ukraine’s various regions and argues that building a modern democratic post-Soviet Ukrainian state is not just a matter of good governance and rule of law at the centre. It also requires an acceptance of bilingualism, mutual tolerance of different traditions, and devolution of power to the regions.

More than any other change of government in Kiev since 1991, the overthrow of Viktor Yanukovych last year [2014 engineered by the US] brought the triumph of the monist view, held most strongly in western Ukraine, whose leaders were determined this time to ensure the winner takes all.

The second crisis arises from the internationalisation of the struggle inside Ukraine which turned it into a geopolitical tug of war. Sakwa argues that this stems from the asymmetrical end of the cold war which shut Russia out of the European alliance system. While Mikhail Gorbachev and millions of other Russians saw the end of the cold war as a shared victory which might lead to the building of a “common European home”, most western leaders saw Russia as a defeated nation whose interests could be brushed aside, and which must accept US hegemony in the new single-superpower world order or face isolation. Instead of dismantling Nato, the cold-war alliance was strengthened and expanded in spite of repeated warnings from western experts on Russia that this would create new tensions. Long before Putin came to power, Yeltsin had urged the west not to move Nato eastwards.

Even today at this late stage, a declaration of Ukrainian non-alignment as part of an internationally negotiated settlement, and UN Security Council guarantees of that status, would bring instant de-escalation and make a lasting ceasefire possible in eastern Ukraine.

The hawks in the Clinton administration ignored all this, Bush abandoned the anti-ballistic missile treaty and put rockets close to Russia’s borders, and now a decade later, after Russia’s angry reaction to provocations in Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine today, we have what Sakwa rightly calls a “fateful geographical paradox: that Nato exists to manage the risks created by its existence”.

The third crisis, also linked to the Nato issue, is the European Union’s failure to stay true to the conflict resolution imperative that had been its original impetus. After 1989 there was much talk of the arrival of the “hour of Europe”. Just as the need for Franco-German reconciliation inspired the EU’s foundation, many hoped the cold war’s end would lead to a broader east-west reconciliation across the old Iron Curtain. But the prospect of greater European independence worried key decision-makers in Washington, and Nato’s role has been, in part, to maintain US [taxpayer funded] primacy over Europe’s foreign policy.

From Bosnia in 1992 to Ukraine today, the last two decades have seen repeated occasions where US officials pleaded, half-sincerely, for a greater European role in handling geopolitical crises in Europe while simultaneously denigrating and sidelining Europe’s efforts. Last year’s “Fuck the EU” comment by Victoria Nuland, Obama’s neocon assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs, was the pithiest expression of this.

Sakwa writes with barely suppressed anger of Europe’s failure, arguing that instead of a vision embracing the whole continent, the EU has become little more than the civilian wing of the [military] Atlantic alliance.

Within the framework of these three crises, Sakwa gives the best analysis yet in book form of events on the ground in eastern Ukraine as well as in Kiev, Washington, Brussels and Moscow. He covers the disputes between the “resolvers” (who want a negotiated solution) and the “war party” in each capital.

He describes the rows over sanctions that have split European leaders, and points out how Ukraine’s president, Petro Poroshenko, is under constant pressure from Nuland’s favourite Ukrainian, the more militant Yatsenyuk, to rely on military force.

As for Putin, Sakwa sees him not so much as the driver of the crisis but as a regulator of factional interests and a temporiser who has to balance pressure from more rightwing Russian nationalists as well as from the insurgents in Ukraine, who get weapons and help from Russia but are not the Kremlin’s puppets.

Frontline Ukraine highlights several points that have become almost taboo in western accounts: the civilian casualties in eastern Ukraine caused by Ukrainian army shelling, the physical assaults on leftwing candidates in last year’s election and the failure to complete investigations of last February’s [2014] sniper activity in Kiev (much of it thought to have been by anti-Yanukovych fighters) or of the Odessa massacre in which dozens of anti-Kiev protesters were burnt alive in a building set on fire by nationalists or clubbed to death when they jumped from windows.

The most disturbing novelty of the Ukrainian crisis is the way Putin and other Russian leaders are routinely demonised. At the height of the cold war when the dispute between Moscow and the west was far more dangerous, backed as it was by the danger of nuclear catastrophe, Brezhnev and Andropov were never treated to such public insults by western commentators and politicians.

Equally alarming, though not new, is the one-sided nature of western political, media and thinktank coverage. The spectre of senator Joseph McCarthy stalks the stage, marginalising those who offer a balanced analysis of why we have got to where we are and what compromises could save us. I hope Sakwa’s book does not itself become a victim, condemned as insufficiently anti-Russian to be reviewed.”

"Jonathan Steele is a former Guardian Moscow correspondent, and author of Eternal Russia: Yeltsin, Gorbachev and the Mirage of Democracy. To order Frontline Ukraine for £15.19 (RRP £18.99), go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846."

..........

No comments:

Post a Comment