|

| Yeltsin and Bill Clinton, 1994, at Kremlin, AP |

After Soviet Union breakup US believed Russia was “ours to lose.”

“The New York Times called it “a victory for Russia.” In fact, it was the opposite: a victory by a foreign power that wanted to place its candidate in the Russian presidency.” Yeltsin allowed looting of Russia’s assets.

8/19/2018, “How to interfere in a foreign election,“ Boston Globe, Stephen Kinzer, opinion

“For one of the world’s major powers to interfere systematically in the presidential politics of another country is an act of brazen aggression. Yet it happened. Sitting in a distant capital, political leaders set out to assure that their favored candidate won an election against rivals who scared them. They succeeded. Voters were maneuvered into electing a president who served the interest of the intervening power. This was a well-coordinated, government-sponsored project to subvert the will of voters in another country — a supremely successful piece of political vandalism on a global scale.

The year was 1996. Russia was electing a president to succeed Boris Yeltsin, whose disastrous presidency, marked by the post-Soviet social collapse and a savage war in Chechnya, had brought his approval rating down to the single digits. President Bill Clinton decided that American interests would be best served by finding a way to re-elect Yeltsin despite his deep unpopularity. Yeltsin was ill, chronically alcoholic, and seen in Washington as easy to control. Clinton bonded with him. He was our “Manchurian Candidate.”

|

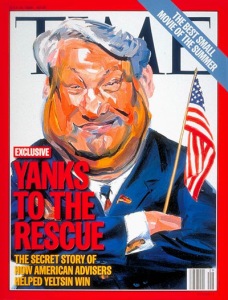

| 7/15/1996 cover |

Part of the American plan was public. Clinton began praising Yeltsin as a world-class statesman. He defended Yeltsin’s scorched-earth tactics in Chechnya, comparing him to Abraham Lincoln for his dedication to keeping a nation together. As for Yeltsin’s bombardment of the Russian Parliament in 1993, which cost 187 lives, Clinton insisted that his friend had “bent over backwards” to avoid it. He stopped mentioning his plan to extend NATO toward Russia’s borders, and never uttered a word about the ravaging of Russia’s formerly state-owned economy by kleptocrats connected to Yeltsin. Instead he gave them a spectacular gift.

Four months before the election, Clinton arranged for the International Monetary Fund to give Russia a $10.2 billion injection of cash. Yeltsin used some of it to pay for election-year raises and bonuses, but much quickly disappeared into the foreign bank accounts of Russian oligarchs. The message was clear: Yeltsin knows how to shake the Western money tree. In case anyone missed it, Clinton came to Moscow a few weeks later to celebrate with his Russian partner. Oligarchs flocked to Yeltsin’s side. American diplomats persuaded one of his rivals to drop out of the presidential race in order to improve his chances.

Four American political consultants moved to Moscow to help direct Yeltsin’s campaign.The campaign paid them $250,000 per month for advice on “sophisticated methods of polling, voter contact and campaign organization.” They organized focus groups and designed advertising messages aimed at stoking voters’ fears of civil unrest. When they saw a CNN report from Moscow saying that voters were gravitating toward Yeltsin because they feared unrest, one of the consultants shouted in triumph: “It worked! The whole strategy worked. They’re scared to death!”

Yeltsin won the election with a reported 54 percent of the vote. The count was suspicious and Yeltsin had wildly violated campaign spending limits, but American groups, some funded in part by Washington, rushed to pronounce the election fair. The New York Times called it “a victory for Russia.” In fact, it was the opposite: a victory by a foreign power that wanted to place its candidate in the Russian presidency.

American interference in the 1996 Russian election was hardly secret. On the contrary, the press reveled in our ability to shape the politics of a country we once feared. When Clinton maneuvered the IMF into giving Yeltsin and his cronies $10.2 billion, the Washington Post approved: “Now this is the right way to serve Western interests....It’s to use the politically bland but powerful instrument of the International Monetary Fund.”

After Yeltsin won, Time put him on the cover—holding an American flag. Its story was headlined, “Yanks to the Rescue: The Secret Story of How American Advisors Helped Yeltsin Win.” The story was later made into a movie called “Spinning Boris.”

This was the first direct interference in a presidential election in the history of US-Russia relations. It produced bad results. Yeltsin opened his country’s assets to looting on a mass scale. He turned the Chechen capital, Grozny, into a wasteland.

Standards of living in Russia fell dramatically. Then, at the end of 1999, plagued by health problems, he shocked his country and the world by resigning. As his final act, he named his successor: a little-known intelligence officer named Vladimir Putin. It is a delightful irony that shows how unwise it can be to interfere in another country’s politics. If the United States had not crashed into a presidential election in Russia 22 years ago, we almost certainly would not be dealing with Putin today.”

“Stephen Kinzer is a senior fellow at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University.”

.......

…………………………Standards of living in Russia fell dramatically. Then, at the end of 1999, plagued by health problems, he shocked his country and the world by resigning. As his final act, he named his successor: a little-known intelligence officer named Vladimir Putin. It is a delightful irony that shows how unwise it can be to interfere in another country’s politics. If the United States had not crashed into a presidential election in Russia 22 years ago, we almost certainly would not be dealing with Putin today.”

“Stephen Kinzer is a senior fellow at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University.”

.......

Added: US happily interfered in Russia’s 1996 presidential election: “The Americans were “vital,” says Mikhail Margolev, who coordinated the Yeltsin account at Video International…. For four months, a group of American political consultants clandestinely participated in guiding Yeltsin’s campaign."

“Yanks to the Rescue,” Time Magazine Boris Yeltsin cover, July 15, 1996. Re-published 6/24/2001, “Rescuing Boris,” Time, Michael Kramer

|

| 7/15/1996 cover |

“The [GAO] audit team concluded, for example, that the U.S. government exercised “favoritism” toward Harvard, but this conclusion and the supporting documentation were removed from the final report.…The very people who were supposed to be the trustees of the system not only undercut the aid program’s stated goal of building independent institutions but replicated the Soviet practice of skimming assets to benefit the nomenklatura….

After seven years of economic “reform” financed by billions of dollars in U.S. and other Western aid, subsidized loans and rescheduled debt, the majority of Russian people find themselves worse off economically. The privatization drive that was supposed to reap the fruits of the free market instead helped to create a system of tycoon capitalism run for the benefit of a corrupt political oligarchy that has appropriated hundreds of millions of dollars of Western aid and plundered Russia’s wealth.”…

………………

Added: “One reason why Yeltsin was the West’s darling—while Mr. Putin is the target of virulent attacks–was that his

policies perfectly suited the Western agenda for Russia, a

superpower-turned economic and military weakling, a subservient client

state and a source of cheap energy and minerals. By

contrast, Russia’s resurgence under Mr. Putin is seen as upsetting the

global balance of power and threatening the U.S. unipolar model.”

………………

3/20/2008, “Why the West loved Yeltsin and hates Putin,“ thehindu.com, Vladimir Radyuhin

……………..

“One reason why Yeltsin was the West’s darling—while Mr. Putin is the target of virulent attacks–was that his policies perfectly suited the Western agenda for Russia, a superpower-turned economic and military weakling, a subservient client state

and a source of cheap energy and minerals. By contrast, Russia’s

resurgence under Mr. Putin is seen as upsetting the global balance of

power and threatening the U.S. unipolar model….[Link, Yeltsin Time cover, “Yanks to the Rescue,” 7/15/1996]

In Russia, Yeltsin is associated with plunging the country into chaos, reducing

a majority of Russians to abject poverty and awarding the country’s

oil, gas and other mineral riches to a handful of rapacious oligarchs,

who plundered Russia and played Kremlin powerbrokers.

The West lauded him as the “father of Russian democracy” who buried communism. Yeltsin remained “Friend Boris” to the West even after he sent tanks to blast his political opponents from Parliament in 1993. In Russia, he faced impeachment charges for this and other “crimes against the nation.”… Mr. Putin’s “controlled democracy” involves centralisation of power, government control over most electronic and some printed media, and Kremlin-supervised grooming of political parties. This policy helped to curb the chaos of the 1990s and bring about political stability that has underpinned economic growth.

At the same time, the communist-era restrictions on personal freedoms are gone. Russians can choose where to live, what books to read and how much money to earn. They are free to marry foreigners and emigrate. They love travelling abroad, fondly drive Fords, Mercedes and Toyotas, and shop for Western goods in the crowded malls lining the streets of Russian cities. The West has denied Mr. Putin’s Russia any democratic credential because it “challenges the prerogative of the dominant democratic powers, in practice the U.S., to judge what is and what is not democratic,” says Russia expert Vlad Sobell of the Daiwa Institute of Research.

The West lauded him as the “father of Russian democracy” who buried communism. Yeltsin remained “Friend Boris” to the West even after he sent tanks to blast his political opponents from Parliament in 1993. In Russia, he faced impeachment charges for this and other “crimes against the nation.”… Mr. Putin’s “controlled democracy” involves centralisation of power, government control over most electronic and some printed media, and Kremlin-supervised grooming of political parties. This policy helped to curb the chaos of the 1990s and bring about political stability that has underpinned economic growth.

At the same time, the communist-era restrictions on personal freedoms are gone. Russians can choose where to live, what books to read and how much money to earn. They are free to marry foreigners and emigrate. They love travelling abroad, fondly drive Fords, Mercedes and Toyotas, and shop for Western goods in the crowded malls lining the streets of Russian cities. The West has denied Mr. Putin’s Russia any democratic credential because it “challenges the prerogative of the dominant democratic powers, in practice the U.S., to judge what is and what is not democratic,” says Russia expert Vlad Sobell of the Daiwa Institute of Research.

According to the petrified “ideological orthodoxy” of the West, “modern democracy was incubated predominantly in the Anglo-Saxon culture and, following the defeat of totalitarian empires in the 20th century, it was spread by the victorious powers throughout Western Europe and Japan,” and more recently in the former Soviet Union and also initially in Yeltsin’s Russia.

The rise of new Russia has undermined America’s self-arrogated right to decide what is good and what is evil, to award marks for good or bad behaviour, and to impose “democratic transformation” on other nations, either by war as in Iraq, or through “colour revolutions” as in Georgia and Ukraine.

If Mr. Putin’s Russia is accepted as an emerging democracy, rather than as a successor to the “evil empire,” it will be difficult to justify the new containment policy the U.S. has set in train, surrounding Russia with a ring of military bases and missile interceptors. Nor would one be able to easily dismiss Moscow’s criticism of the aggressive and arrogant U.S. behaviour across the world.

As Mr. Putin asked in his famous Munich speech, if Russia could carry out a peaceful transition from the Soviet regime to democracy, why should other countries be bombed at every opportunity for want of democracy? Hence the Herculean effort of Western opinion-makers to paint everything Mr. Putin does in evil colours.

The U.S. State Department’s annual report on human rights in 2007 mounted the harshest attack yet on the state of freedom in Russia, while the U.S. Freedom House listed it as one of the several “energy-rich dictatorships.” Republican presidential candidate John McCain has accused Mr. Putin of “trying to restore the old Russian empire,” and “perpetuating himself in power” by installing his “puppet” Dmitry Medvedev in the Kremlin.

In sticking labels on Russian leaders, the West outrageously ignores the opinion of the Russian people. Russians showed what they thought of Yeltsin’s legacy when they voted out of Parliament twice in recent years the liberal parties that had supported his policies in the 1990s. They demonstrated their support for Mr. Putin’s policies when they triumphantly re-elected him for a second term in 2004 and when they overwhelmingly voted for Mr. Medvedev in March 2008.

Mr. Putin bluntly told the West that its criticism of his policies would not induce his successor to strike a softer posture in foreign policy. “I am long accustomed to the label by which it is difficult to work with a former KGB agent,” Mr. Putin said at a recent press conference. “Dmitry Medvedev will be free from having to prove his liberal views. But he is no less a Russian nationalist than me, in the good sense of the word, and I do not think our partners will find it easier to deal with him.”

For his part, Mr. Medvedev, while pledging that “freedom in all its manifestations — personal freedom, economic freedom and, finally, freedom of expression” — would be “at the core of our politics,” said democratic values would be adopted in line with Russia’s “national tradition.””

| .............. |

No comments:

Post a Comment